SIGNIFICANCE OF THE LUNAR WEEK

A-Quest-for-Creation Answers

Last Revision: February 19, 2015 (5)

Copyright © 2008-2026

__________________________________________

CHAPTER 1

THE LUNAR WEEK

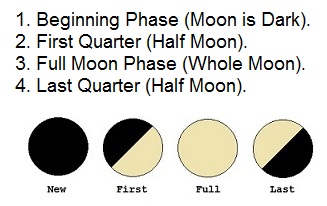

Lunar-quarter days are marked on many, if not most, of the calendars and almanacs that are published throughout the Western world. Even so, the turn of the lunar quarter does generally go unnoticed by most. Whether ignored or not, the Moon routinely generates four easy to identify phases throughout its monthly transit of the Earth --

Take note here that the quarter-phase of the Moon (the cycle of the lunar week) happens to revolve in pace with a rate that is about equal to seven and one-third days. The turn over of the lunar week (the lunar quarter) is consequently a bit slower or longer than an ordinary week cycle of 7 days.

But why should anyone be concerned with the peculiar turn of the lunar week . . . or why give notice to a time unit that is inherently defined by the Moon?

One of the best of the possible answers to this kind of question is that the time span occupied by the lunar week points to a time-tracking system that is rational in its design. Essentially, the lunar-week cycle does rather clearly indicate that the Earth and Moon are spinning/orbiting objects BOTH working together for a purpose. Subsequently presented chapters then have a primary focus upon the lunar week in the context of a lunisolar system that is functional in its design. Of special significance here is that a time unit equal to the lunar week can be recognized to conjoin (exactly) with the turn of the solar day. The lunar week can likewise be recognized to cycle (eternally) in perfect interface with the annual transit of the Sun. More amazing about the Earth and Moon interface is a clear indication of '7-set' design--where 7 sets of weeks, 7 sets of months, and 7 sets of years are all inherently defined from out of the spin and orbital phenomenon.

In addition to its role in defining a lunisolar system that is functional in its design, the lunar week can be recognized to have additional significance in defining a religious itinerary that now is followed by adherents numbering millions in regions of the East. To be more specific, "the Uposatha is the Buddhist sabbath day, in existence from the Buddha's time (500 BCE), and still being kept today in Theravada Buddhists countries" (Wikipedia). Among the precepts that define this 'day of observance' is the holding of a fast and the keeping of an all night vigil. "In general, Uposatha is observed about once a week in accordance with the four phases of the moon: the new moon, the full moon, and the two quarter moons in between. In some communities, only the new moon and full moon are observed as uposatha days." (ibid.). The cited set of evening liturgy that is practiced in parts of Asia today is strikingly similar to lunar liturgy that was subscribed to by more primal priest-kings (especially those who were resident in the Middle East). This custom of fasting and of holding a night vigil in pace with certain of the Moon's phases can be recited from numerous passages of early literature. The current presentation thus also has a focus upon the lunar week and its roll in the scheduling of religious liturgy (past and modern).

Of special significance about a schedule of weeks is that Hebrew writings produced in and prior to the first century are graphic in showing that the priesthood held knowledge of a harvest cycle straddling 7 lunar weeks. Texts that were circulated among primal Christians do likewise show that a segment of 1st-century astronomers would have understood the turn of the 7th lunar week in the context of both a sacred and a secular calendar. Among both Babylonians and Hebrews, the cited fast and vigil appears to have routinely been held for the primary purpose of renewing a post-flood covenant. Adherence to this respective ordinance (the keeping of an Asartha) can also be recognized from among the tenets that were taught by the early Christians.

What is unique about the Middle Eastern tradition of holding an Asartha (or Atsereth) is that the priests appear to have tracked or accounted for the unit of the lunar week in multiples of seven (or by sevens). Essentially, a tally, or a count of 7 lunar weeks (a pentecontad cycle) was perceived to have been succeeded by a subsequent cycle of 7 lunar weeks (the next pentecontad cycle). Subsequently presented sections will then explore in depth the lunar-week schedule by which liturgy was performed under the old Jerusalem Temple.

The topic material presented will lead the reader to ultimately conclude that the Temple priesthood did almost surely hold unusual, even advanced, knowledge of a lunisolar system. More significantly, the reader will be presented with a systems view of the spin rate of the Earth and of the two apparent orbits (Moon and Sun). A given conclusion that can be arrived at from a systems perspective of the Earth and Moon is that the spin and orbital configuration has resulted from special creation.

CHAPTER 2

SETS OF SEVENS

A rational system for tracking time can be recognized from out of the spin and orbital phenomenon. Of special significance here is that the length of the tropical year can closely be cross-referenced to a time grid comprised of lunar quarters, or lunar weeks.

What is remarkable about tracking the annual cycle in units of the lunar week is an inherent correspondence with certain number sets. In fact, both solar days and solar years can be cross-referenced to lunar-week cycles that are numbered by sevens (and by multiples of sevens).

This peculiar attribute of '7-set design' becomes easy to recognize through the count of a cycle of 49 months. Of significance here is that after a time traverse of 49 periods, the Moon (on average) does inherently renew right at the same hour and minute of the solar day. A given conclusion from the same rotational alignment of the Earth is that a span of time equal to 49 moons can exactly be divided into solar-day units (where each solar day is equal to 24 hours, or also 86400 seconds).

Please take note here that the lunar month (of 29 days 12 hours, and 44 minutes on the average) if repeated for 49 times does inherently traverse a time span that is almost perfectly equal to 1447 solar days.

THE INTERFACE OF Number of 49 SYNODIC MONTHS * Earth's Rotations __________________________ _________ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 206.71 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 413.43 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 620.14 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 826.86 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 1033.57 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 1240.28 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 1447.00 __________________________ _________ * - Earth's rotation aligns with 49 lunar months.

Thus, it would be a true axiom to state that 49 lunar months (on the average) are equal to a time span that can be divided into an even number of 24-hour days.

It would likewise be a true axiom to state that 1447 days is equal to a time span that can be divided into an even number of lunar months.

This conjunction cycle between the Earth and the Moon every 49 months can easily be demonstrated by almost anyone. The interface can be proven by simply dividing 1447 (days) by 49. The result of the division can then be compared with the span of time occupied by the average lunar month--which is 29.53059 days. Note that a correct answer from performing this math will not differ from 29.53059 by more than 2 seconds!!!

The cited synchronization of Earth's spin with 49 lunar periods is very close (almost exact). Of significance is that the stated interface can be recognized as fully perfect if only the lunar cycle elapsed in 29.53061 days (a tiny bit different from the modern rate of 29.53059 days). The possibility then is that the conjoining of these two cycles may either have once been fully perfect (as in medieval times when ice extended farther from the poles) or when (in the future) the spin-orbital configuration changes. (For more information about the changing spin of the Earth, refer to the subsequently presented Chapter 14).

Please take note from the previously presented paragraphs that a design characteristic of '7-sets' (or '7 times 7') is easy to interpret between the rate of the rotation of the Earth and that of the synodic period of the Moon. This same '7-set' characteristic is likewise easy to recognize from a calendar count of 49 lunar weeks (as is more fully shown in the subsequently presented chapter).

Note that 1447 days divided by the rate of the synodic-month cycle, or 29.53059 days, is equal to 49.0000 lunar months.

CHAPTER 3

A JUBILEE CALENDAR

Of yet further significance about the Earth and Moon interface (and about '7-set design') is that each year cycle can also be modeled into, or represented by, a calendar of lunar weeks. In fact, a rather amazing time interface can be recognized from modeling the annual return into 7 sets of lunar weeks.

The following diagram is consequently presented in an attempt to more clearly illustrate that a time grid of solar years (in 7 sets) can closely be correlated, or cross-referenced, to a calendar count of lunar weeks (in 7 sets).

The shown grid of lunar weeks represents a calendar that can very closely pace the annual return. This respective calendar only requires the endless addition of 1 week each 3rd year--as a perpetual rate of intercalation.

7-Year Number Number of At Each Segment of Years Lunar Weeks 7th Year ------- -------- ----------- -------- 1. 7 7 x 7 x 7 + 1 week 2. 7 7 x 7 x 7 + 1 week 3. 7 7 x 7 x 7 + 1 week 4. 7 7 x 7 x 7 + 1 week 5. 7 7 x 7 x 7 + 1 week 6. 7 7 x 7 x 7 + 1 week 7. 7 7 x 7 x 7 + 1 week ------- -------- ----------- -------- 50th yr 1 7 x 7

For more comprehensive information about the diagrammed calendar--as well a thumbnail sketch of the historical relevance of this particular calendar--refer to Chapter 13.

Of significance about the shown time grid is that a somewhat synonymous description of a year count of '7 sets' is shown in a certain passage of the Bible. The early celebration of '7 sets of 7 years' is clearly depicted in a chapter from the book of Leviticus--as follows:

"And the Lord said . . . When you come into the land which I will give you, let the land keep a Sabbath to the Lord. For six years put seed into your land, and for six years give care to your vines and get in the produce of them; But let the seventh year be a Sabbath of rest for the land, a Sabbath to the Lord; do not put seed into your land or have your vines cut. That which comes to growth of itself may not be cut, and the grapes of your uncared-for vines may not be taken off; let it be a year of rest for the land. And the Sabbath of the land will give food for you and your man-servant and your woman-servant and those working for payment, and for those of another country who are living among you; And for your cattle and the beasts on the land; all the natural increase of the land will be for food. And let seven Sabbaths of years be numbered to you, seven times seven years; even the days of seven Sabbaths of years, that is forty-nine years; Then let the loud horn be sounded far and wide . . . on the day of taking away sin let the horn be sounded through all your land. And let this fiftieth year be kept holy, and say publicly that everyone in the land is free from debt: it is the Jubilee, and every man may go back to his heritage and to his family. Let this fiftieth year be the Jubilee: no seed may be planted, and that which comes to growth of itself may not be cut, and the grapes may not be taken from the uncared-for vines. For it is the Jubilee, and it is holy to you; your food will be the natural increase of the field. In this year of Jubilee, let every man go back to his heritage." (BBE text of Chapter 25:1-12).

Remarkable here is that the Leviticus definition of a 50-year count closely parallels the calendar count shown above--where each 7-year segment of the calendar grid can be metered by a lunar-weeks count. Assigning a number to each calendar week is all that is required; and this means that EACH AND EVERY calendar year can be defined within the context of an identical count of the lunar week (a 7-times-7 count):

_________________________________________ A JUBILEE CALENDAR OF LUNAR WEEKS Note that a leap week each 3rd year is not shown in the following calendar chart. _________________________________________ Seven Years: 49 49 49 49 49 49 49 + 1 Seven Years: 49 49 49 49 49 49 49 + 1 Seven Years: 49 49 49 49 49 49 49 + 1 Seven Years: 49 49 49 49 49 49 49 + 1 Seven Years: 49 49 49 49 49 49 49 + 1 Seven Years: 49 49 49 49 49 49 49 + 1 Seven Years: 49 49 49 49 49 49 49 + 1 Fiftieth Year: 49 _________________________________________ 49--Denotes a year count of 49 lunar weeks. 50-year average = 2473.66667 lunar weeks. Length of lunar weeks = 18262.21 days. Length of 50 years = 18262.11 days.

A given conclusion from the rates shown above in the calendar diagram then is that each passing year can very effectively be metered by simply counting out lunar weeks.

A calendar of lunar weeks is thus automatic or inherent when a lunar week is leaped each 3rd year as a perpetual rate. (Note that the shown grid of lunar weeks does almost perfectly pace the rate of the solar year through the intercalation of 0.33333 weeks per solar year--as an average rate).

A plausible model (or interpretation) of a lunisolar system is thus easy to formulate from counting out a Moon Cycle (equal to 7 lunar weeks).

CHAPTER 4

WEEKS OF HARVEST

Historical records, including biblical, tend to indicate that certain astronomers who flourished in an era well prior to the 1st century would have been familiar with the cited time track of lunar weeks. To be specific, some of the Jewish texts written in the era of the Temple do clearly mirror the Temple priesthood followed a liturgical schedule that was defined by a cycle of 7 lunar weeks.

Of significance here is that writings produced by Flavius Josephus (a Jewish historian of the 1st century) show that Temple priests of that time period did track a 7-week cycle. When describing a harvest calendar that was then followed, Josephus made mention of a 50-day count traversing 7 lunar weeks--as follows:

" . . . when the Sun is in Aries . . . on the 16th day of the [lunar] month . . . they offer the first fruits of their barley . . . When a week of weeks has passed over after this sacrifice . . . on the 50th day, which is Pentecost . . . they bring to God [sacrifices] nor is there anyone of the [subsequent] festivals, but in it [= the 50th] they offer . . . " (Based upon Whiston's translation of 'Antiquities of the Jews', Book 3, Chapter 10, 5-7).

The Josephus record shows that the priests counted out a cycle of 7 weeks AFTER a barley offering was presented (on the 16th day of a specific lunar month). The cited 50-day count did therefore begin on a day that came after the full phase of the Moon.

One of the conclusions that can be arrived at from the detail provided by Josephus is that the end of the 50-day count would inherently have coincided with a quarter phase of the Moon. Furthermore, each of the intervening weeks of the 50-day count can be recognized to have passed in line with a lunar quarter. In essence, the priests can be recognized to have tracked a full cycle of 7 lunar weeks between the first fruits presentation and the feast of Pentecost.

Note that because each lunar week spans a unit of time that is a bit longer than an ordinary week of 7 days then a number of 50 days can ALWAYS be counted between the end of the 1st day of any given lunar week and the beginning of the 7th day of the 7th lunar week. In essence, 7 lunar weeks is inherently LONGER, or FULLER, when compared with a day count of 7 regular weeks.

____________________________________ LEVITICAL HARVEST COUNT (from the record of Josephus) ____________________________________ A sheaf was waved after 1st full Moon 1st week counted 2nd week counted 3rd week counted 4th week counted 5th week counted 6th week counted 7th week counted New grain celebrated at quarter Moon ____________________________________

The indicated priestly adherence to a harvest schedule that was defined by the lunar week can further be recited from a treatise penned by another 1st-century Jewish writer:

"Don't the fruits of cultivated crops and trees grow and come to maturity through the orbits of the Moon . . . ?" ('The Special Laws, Part 2', Philo Judaeus, based upon Yonge's translation).

Here, the annual harvest is again shown to have been conducted in coincidence with a span of time that was uniquely tracked. This passage of early-written text does minimally indicate that the annual harvest was NOT scheduled in the context of an ordinary week cycle (of 7 running days).

Other passages from Jewish literature written in the era of the late Temple do likewise show that contemporary priests did then conduct the annual harvest around a lunar-quarter schedule. In example, a passage from 'The Special Laws, Part 1' indicates that members of the priesthood would have been familiar with a harvest itinerary that was predicated upon the phases of the Moon:

"[The Moon] receives the perfect shapes in periods of 7 days--the half-Moon in the first 7 day period after its conjunction with the Sun, full Moon in the second; and when it makes its return again [= after the full Moon], the first is to half-Moon, then it ceases at its conjunction with the Sun . . . the finest grain flour mixed with oil . . . and wine in stipulated amounts [are periodically offered] . . . The reason is that even these are brought to maturity by the orbits of the Moon in the annual seasons, especially as the Moon helps to ripen fruits; grain and wine and oil . . . " (authored by the Jewish writer: Philo Judaeus at about the turn of the Common Era, translation based upon Yonge).

The quoted text from 'The Special Laws' reflects that the author understood the Moon to have some kind of a role in the production of grain, wine, and oil.

It here seems of related significance that quite a number of passages in the Bible do indicate that the beginning of the harvest was specially commemorated; and that the harvest was subsequently commemorated in weekly stages.

"[God] . . . giveth rain, both the former and the latter, in his season: he reserveth unto us the appointed weeks of the harvest". (AV text of Jeremiah Chapter 5:24).

As is further shown below, the weeks that were appointed for the harvest (or harvests) were understood to encompass not just a single cycle of 7 lunar weeks--but multiple cycles. To be more specific, the first cycle of 7 weeks was apparently reserved for the production of grain. A subsequent cycle of 7 weeks is additionally indicated from the historical record. (This respective cycle was allocated for the production of wine). Yet a third cycle of 7 weeks is manifested from the ancient texts. (This time span was reserved for the production of oil). Thus, certain of the texts that were produced (and reproduced) in the era of the Temple do show that first fruits of grain, wine, and oil were sequentially processed right in line with a time cycle of 7 weeks.

Perhaps the best example of this cyclical count of 7 weeks can be recited from a portion of 11QTemple Scroll. The following passage is very clear in showing how that the priests would have supervised the production of first fruits (grain, wine, and oil) in concert with multiple cycles of 7 weeks:

"You must count . . . 7 COMPLETE Sabbaths from the day of presenting the sheaf . . . to the morrow of the 7th Sabbath . . . count [50] days . . . [Then] bring a new grain-offering . . . it is the feast of Weeks and the feast of Firstfruits, an everlasting memorial . . . From the day when you bring the new grain-offering . . . 7 FULL Sabbaths . . . count 50 days to the morrow of the 7th Sabbath. [Then present] new wine for a drink-offering . . . Count from that day . . . 7 FULL Sabbaths; until the morrow of the 7th Sabbath count 50 days . . . then offer new oil . . . " (my paraphrase).

The content of the 11QTemple Scroll can be stated to be rare or unique in comparison with most other Hebrew documents (even among those that have been rediscovered). Nonetheless, some rather detailed instructions are given for conducting the first fruits harvest. According to the author (or authors) of this scroll, the processing of new grain, new wine, and new oil required adherence to always a COMPLETE or a FULL count of 7 Sabbaths. For each one of the three harvests, a special day was invariably celebrated right on "the morrow of the 7th Sabbath".

_____________________________________ SCHEDULING OF FIRST FRUITS _____________________________________ 1. 7 Sabbaths for New Grain 2. 7 Sabbaths for New Wine 3. 7 Sabbaths for New Oil _____________________________________ An offering of grain, then wine, and then oil was presented in the predawn hours on each one of the 7th Sabbaths

The cited description of a FULL Sabbath count [Hebrew: tamiym] that ended at the break of day on the 7th Sabbath is just about identical to the intervening 50-day count shown in the Bible book of Leviticus (refer to the 23rd chapter). A comparison of the sacrificial rates for the festival of weeks that is listed in Leviticus, Numbers, and in the writings of Josephus tends to confirm that the first fruits type of the feast of weeks was celebrated with an additional rate of sacrifice. Of related interest here is that the 11QTemple Scroll and also 'The Book of Jubilees' do both show that the first fruits were believed to have a dual or a double significance. Each respective festival day was understood to pertain to both the feast of weeks and the feast of the first fruits.

When the content of the 11QTemple Scroll is compared with the content of the Bible, it becomes manifest that the production of grain, wine and oil is also listed in that same order in a number of the Bible passages. The order of grain, wine, and oil can be recited from the following Bible verses: Deuteronomy 7:13; 11:14; 12:17; 14:23; 18:4; 28:51; 1 Chronicles 9:29; 2 Chronicles 2:15; 31:5; 32:28; Ezra 6:9; Nehemiah 10:37; 10:39; 13:5; 13:12; Jeremiah 31:12; Hosea 2:8; 2:22; and there are other verses.

A sequence of 3 festivals, each spaced 7 weeks apart, can also be identified from the following scrolls recovered at Qumran: 4Q325, 4Q326, 4Q327, 4Q394; where English translations can be found in: 'Dead Sea Scrolls A New Translation', by Michael Wise, Martin Abegg, Jr., and Edward Cook. Of significance here is that some of the Qumran scrolls--while they do indicate the track and celebration of 7 weeks in a three-fold sequence--do not indicate that a 50th day was separately counted out. Essentially, the 7-week cycle that was counted at Qumran was predicated upon nothing more than an ordinary week cycle of 7 running days. This then means that the harvest itinerary that was followed by contemporary Temple priests could not have quite been the same as the 7-weeks count that was followed at Qumran. In fact, liturgical interpretations held at Qumran--when compared with interpretations subscribed to by the more traditional priests--point to quite a number of differences. (Most of the indicated differences concern the Temple's adherence to a lunar calendar).

The priestly reckoning of a cycle of 7 weeks (in association with a celebrated 50th day) is shown in the Hagigah Tractate (section 17a) of the Babylonian Talmud. In a note to that section, the translator (Rabbi Abrahams) wrote that the Sadducees understood each 7th day of the Leviticus count of 50 days to be a literal Sabbath. This respective note seems significant for coming to better understand certain opinions and interpretations held by members of the primal Temple priesthood.

As is more fully shown in the subsequently presented Chapter 7, the set of 7 weeks that orthodox priests counted in association with both the Moon and the first fruits (of grain, wine, and oil) certainly was understood in the context of time that was considered to be holy. However, those 7-week time segments that defined when first fruits of grain, wine and oil were presented were also understood to pertain to a covenant that was made with all mankind (as descended from Noah). This worldwide covenant was consequently considered among Jews of the Temple Era to pertain to time that was "less blessed and holy" than time defined by a covenant that pertained to the celebration of each 7th-day (a covenant that was given exclusively to Israel).

As far as the celebration of those 'lesser' Sabbaths--those that pertained to the harvest of first fruits--the 'weeks of harvest' were counted out by members of the priesthood (and by religious Jews), and then an Asartha (an Atsereth) was held in the nighttime hours. Again, more information about the holding of an Atsereth is shown in subsequently presented Chapter 7.

Of additional significance here is that a time cycle of 50 days appears to have likewise been tracked in regions of the ancient Middle East (and by cultures other than Israelite). To be more specific, a pentecontad unit [ = the 'h.' or the 'hamushtum'] is listed on various of the recovered cuneiform tablets (some pertaining to the Old Assyrian Period).

More information about the 'hamushtum' is shown in a 20th century publication: 'Origin of the Week and the Oldest Asiatic Calendar', by H. and J. Levvy.

Of special interest here is that the 'h.' or the 'hamushtum' [= probably a period of 50 days] was sometimes used in association with the agricultural cycle--as follows:

- A time for swinging the sickle [= 7 weeks for New Grain?

- A period for gathering grapes [= 7 weeks for New Wine?].

- Season for harvesting figs [= 7 weeks for New Oil?].

The 'h,' or the 'hamushtum' is also sometimes shown in combination with the time of a 'sapattum' (ibid). Please take note here that the term: 'sapattum' would probably have been understood among the ancients to be about equivalent to the English word: 'cease'. What is more certain than the meaning of this term is that the 'sapattum' would have been understood as 'a period of time between the waxing and waning phases of the Moon'.

In summary to the above, writings from the era of the Temple show that the priests would have understood the weeks of the first harvest right in concert with 7 lunar quarters. (Records show it was after a "50 count" of days in the predawn hours that sacred liturgy was enacted by the priesthood).

____________________________________ CALENDAR OF HARVEST OFFERINGS * ---------- ------------------- OFFERING TIME OF OFFERING ---------- ------------------- New Grain 7 weeks after Sheaf New Wine 7 weeks after Grain New Oil 7 weeks after Wine ____________________________________ * - Offerings for grain, wine, and oil came after the wave sheaf.

Of significance about the "weeks of harvest" is that the time in-between 7 lunar weeks is inherently GREATER or FULLER than the length of 7 regular weeks.

CHAPTER 5

AN ENDLESS CYCLE

A collection of Hebrew axioms and formulas for resolving the courses of the Earth and Moon are available for modern analysis. This ancient collection is represented in passages of a rediscovered manuscript attributed to Enoch (one of the Bible patriarchs). In fact, an entire section of the Enoch literature (refer to the Laurence translation, chapter 71 to 82) has a focus upon "the revolutions of the heavenly luminaries". (The cited portion of text that attempts to mathematically quantify the spin and orbital phenomenon is known as Enoch's astronomical book).

The content of the collection attributed to Enoch is unique in that a rather comprehensive description of tracking 'time stations' is embedded in the astronomical section.

Early-held knowledge of the location of time stations for both the Sun and the Moon seems very apparent from the following selected portions of 'The Ethiopian Enoch', by Laurence:

[Chapter 71:] "The book of the revolutions of the luminaries of heaven, according to . . . their respective periods . . . and their respective months . . . [Skipping to Chapter 73:] . . . I beheld their stations . . . according to the fixed order of the months the Sun rises and sets . . . thirty days belonging to the Sun . . . The Moon brings on all the years exactly, that their stations may come neither too forwards nor too backwards a single day; but that the years may be changed with correct precision . . . The year then becomes truly complete according to the station of the Moon . . . " .

From the Enoch literature, it is apparent that the ancients did once time track a "station" of the Sun--probably in association with a cycle of 30 days. Portions of text from the astronomical book also make it clear that a "station to the Moon" was time tracked inside of the year cycle. In essence, in addition to a station of the Sun, Enoch's astronomical book also describes an associated station of the Moon.

"The year then becomes truly complete according to the station of the Moon, and the station of the Sun" (ibid.).

According to the astronomical book, in addition to a station of the Sun, a station of the Moon also belongs among (pertains to) the revolutions of the heavenly luminaries.

Thus, the detail given for time stations indicates that some among the ancients held knowledge of an effective method for tracking each annual return (the year cycle). Of significance here is that Enoch's axiom for metering the year cycle was stated only in terms of the revolution of two time stations:

- A day or station defined by the Moon.

- A day or station defined by the Sun.

Of additional significance is that other portions of the Enoch literature indicate the cited station or day of the Moon might have been tracked in place, or in position, with a sequence of the lunar quarters. This positioning of a station or day of the Moon in correspondence with a cycle of the lunar-quarter phases is easy to interpret from the following portions of the cited astronomical book:

"(Chapter 72: verse 3) . . . [the Moon's] light is a seventh portion from the light of the Sun . . . . (verse 6) Half of it is in extent seven portions . . . its light is by sevens . . . (verse 8-10) On that night, when it commences its period . . . it is dark in its fourteen portions . . . During the remainder of its period its light increases to fourteen portions [or the Moon's light increases to fourteen portions] . . . (Chapter 73: verse 4) In each of its two seven portions it completes all its light [or the Moon reaches the phase of full illumination in two seven portions] ." (ibid.).

A more in depth research of Enoch's astronomical book leads to the ultimate conclusion that the cited station or day of the Moon was probably tracked in association with a cycle of 7 lunar quarters or 7 lunar weeks. The clue to coming up with a more explicit definition of the station of the Moon from the astronomical book can seemingly be found in Chapter 73 in the portion of text that provides detail of the Moon and its lag of 50 days. ("To the Moon alone . . . it has fifty days . . . ").

It can thus ultimately be interpreted that primal priest-astronomers did once reckon lunar weeks and were knowledgeable of a station or day of the Moon (in addition to the cited station of the Sun). The station of the Moon appears to have been tracked in correspondence with a time-span of 7 lunar quarters or 7 lunar weeks.

The description of a station or a day of the Moon from the Enoch texts is then significant and tends to indicate the early use of the following axiom or time formula:

The revolutions of the heavenly luminaries define a station or day that pertains to the Moon. This station or day reoccurs in a cycle of 7 lunar weeks (an endless rate).

Of significance here is that each year cycle (year . . . after year . . . after year . . . ) can be correlated to a day count that does never vary as long as those days that reoccur in the position of each 7th lunar week are leaped over (or are not counted).

Note that if the count of one day in each cycle of 7 lunar weeks is eternally accounted for (as separate from the other days) then this respective count is inherently equal to 7.0676 days per year. In addition, if the count of one day in each month of 30 days is forever accounted for (as separate from other days) then this respective count is inherently equal to 12.17474 days per year (as an average rate). These two rates of set-apart days (or time stations) are then equal to an average rate of 19.24232 days per year. Thus, if 19.24232 days per year (on the average) are tracked apart from all other days that comprise the time stream then the length of each passing solar year can effectively be measured and metered out in correspondence with a number count that is always equal to 346.000 of the other days.

It is then clear that the turn of each tropical year can exactly be defined (as an average definition) in the context of nothing more than forever tracking a station of the Sun (each 30th day) and also eternally tracking a station of the Moon (at every 7th lunar week). In essence, within the context of both monthly and weekly renewals, each passing tropical year (which is 365.24 days in length) can be understood to revolve in perfect pace with an identical count of day units (346 days). To be completely specific, an accounting of 346 days with the addition of renewal days (19.24 days) is inherently equal to the length of the annual circle or year.

Thus, certain among the axioms and time formulas written down in Enoch's astronomical book are proven as remarkably accurate. The solar circle (365.24219 days) inherently does contain a station or day of the Sun (a perpetual rate of one in a 30-day cycle) and also a station or day of the Moon (a perpetual rate of one in a cycle of 7 lunar weeks).

_________________________________ ENDLESS CYCLE OF 7 LUNAR WEEKS _________________________________ Lunar quarter 1 (lunar week 1) Lunar quarter 2 (lunar week 2) Lunar quarter 3 (lunar week 3) Lunar quarter 4 (lunar week 4) Lunar quarter 5 (lunar week 5) Lunar quarter 6 (lunar week 6) Lunar quarter 7 (lunar week 7) _________________________________ The count of 1 day is skipped, or leaped over, in each 7-week cycle.

Especially significant about the astronomy of Enoch is the revelation of a day-count model that can exactly account for each passing tropical year. (This accounting of the year cycle only requires a separated time track of Sun and Moon stations).

CHAPTER 6

HARVEST CELEBRATION

A number of passages of ancient Hebrew literature tend to further indicate that the Levitical priesthood would have celebrated liturgy in pace with the turn of the lunar week.

Of significance here is the historical record rather clearly reflects that the priests understood the lunar week within the context of defining a series of harvest festivals--where 7 full Sabbaths were accounted for to memorialize the production of new grain, new wine, and new oil. (For pertinent information of the 7-weeks count, refer to the previous chapters).

The production of new grain, new wine, and new oil in pace with the turn of the lunar week is perhaps most graphically shown in the following passage of 'The Special Laws':

"[The Moon] receives the perfect shapes in periods of 7 days . . . [and] helps to ripen fruits; grain and wine and oil . . . " . (This passage from Part 1 was written at about the beginning of the Common Era by Philo Judaeus, translation based upon Yonge).

As far as the scribe (or count) of 7 weeks (of harvest), or 7 Sabbaths, perhaps the best example can be recited from passages of Leviticus--where in Chapter 23 of the Hebrew version, a 7-weeks count was described to begin or to commence with 'mochorath h+shabbath' (which is presumed to mean the morrow of the Sabbath):

"Your scribe or number ('caphar') must extend from the morrow ('mochorath') to the Sabbath (h+shabbath) . . . " (Leviticus 23:15).

From this beginning or origin, it was essential that a number count encompass a time span equal to 7 whole Sabbaths:

" . . . 7 Sabbaths shall be whole or entire . . . ". (Note here that the Hebrew Bible includes the word 'tamiym' to designate a Sabbath that is wholly or fully counted).

A 'new' offering was ultimately presented on the next 'mochorath' after 50 numbered days. (Only after a full or a complete count had been accomplished was a special renewal day celebrated).

Note here that the cited offering was commanded to be 'new'. The word that is translated from the original Hebrew text as 'new' comes from only 3 Hebrew consonants (pronounced something like 'ch' 'd' 'sh') in that vowels do not appear in the original Hebrew Bible. Vowels were eventually added/inserted into the original Hebrew text by Jewish scribes who flourished in the first centuries of the Common Era. Consequently, throughout the more modern Masoretic texts the original 3 consonents were revised to become 'chadesh' or 'chodesh'. This word is used throughout the Hebrew Bible in reference to a time cycle or the renewal of a time cycle.

As far as scribing (or numbering) a 'full' count of 7 harvest weeks, it here seems significant that early-written texts have detail of an annual count of days that included the reckoning of a station of the Moon as well as the reckoning of a station of the Sun. (For additional information about counting the annual return in the context of time stations, refer to the previously presented chapter). What is significant here is that when each day of the Sun is never counted as a regular week day then each and every revolution of 50 days can be recognized to inherently keep pace with 7 lunar quarters.

So, the ancients could have effectively metered and measured out each passing tropical year by accounting for Sun and Moon stations (as previously shown) and they could also have accurately charted the return of each quarter phase of the Moon (on average) by accounting for Sun and Moon stations.

Thus, a method of 'day counting' the tropical year and also the lunar quarter (on average) is manifested from a simple method of accounting for those days that correspond with time stations of the Sun and Moon.

Take note here that the cited station or day of the Sun (1 day every 30 days) inherently occupies 3.33333 percent of the time stream.

When the count of this day is subtracted from out of all the days that occupy the time stream then a count equal to 50 days (on average) can be recognized to exactly straddle a span of time equal to 7 lunar weeks. For more information about the overlay of 50 days with each 7th Moon phase, refer to

The cited day or station of the Moon can therefore quite effectively be tracked by simply scribing or numbering a cycle of 50 days (exclusive of the counts of those days that align with the station or day of the Sun).

The previously cited record of Flavius Josephus is more graphic than Leviticus in showing when the harvest count would have began:

" . . . on the 16th day [of the 1st lunar month] . . . they offer the firstfruits of their barley . . . and after this it is that they may publicly or privately reap their harvest . . . When a week of weeks has passed over after this sacrifice, (which weeks contain forty-nine days,) on the fiftieth day, which is Pentecost, but is called by the Hebrews ASARTHA, WHICH SIGNIFIES PENTECOST, they bring to God a loaf, made of wheat flour, of two tenth deals, WITH LEAVEN; and for sacrifices they bring two lambs; and when they have only presented them to God, they are made ready for supper for the priests; nor is it permitted to leave anything of them till the day following. They also . . . [present] a burnt offering . . . for sins; nor is there anyone of the festivals, but in it [= 'Number 50'] they offer burnt offerings; they also allow themselves to rest [hold Sabbath] on everyone of them. Accordingly, the law prescribes in them all what kinds they are to sacrifice, and how they are to rest entirely, and must slay sacrifices, in order to feast upon them. However, out of the common charges, baked bread [was set on the table of showbread], WITHOUT LEAVEN . . . they were baked the day before the Sabbath, but were brought into the holy place on the MORNING OF THE SABBATH, and set upon the holy table, six on a heap, one loaf still standing opposite one another . . . and there they remained till another Sabbath, and then other loaves were brought in their stead, while the loaves were given to the priests for their food, and the frankincense was burnt in that sacred fire wherein all their offerings were burnt also; and so other frankincense was set upon the loaves instead of what was there before . . . " ('Antiquities of the Jews', Whiston, Book 3, Chapter 10, 5-7).

Clear from the writings of Josephus is that the harvest count would have began after a full phase of the Moon (and after the sheaf was waved).

The late 1st-century record thus points right to the day when Pentecost would have then been celebrated. (A given conclusion from the counts shown is that Pentecost would have been celebrated at the turn of a lunar quarter or lunar week).

Unlike the record of Leviticus which shows a specific count of "Sabbaths" relative to the time of observing Pentecost, the above quoted portion from the record of Josephus does not spell out that a count of 7 Sabbaths was performed by the priests. Instead, the Josephus record shows that 'count 50' was "called by the Hebrews ASARTHA, which signifies Pentecost".

This passage is significant in the regard that other portions of the Hebrew record show that the occasion of an Asartha would have been understood to correspond with the time of a quarter phase of the Moon. The historical usage of the term "asartha" (or "atsereth") thus tends to further prove that the harvest schedule of the Temple would have been predicated upon an accounting of lunar-quarter weeks (and not a count of the regular week).

To here be more specific, the observance of Asartha (or Atsereth) can be recited several times from passages of the Hebrew Bible. For example, the holding of a fasting assembly (Atsereth) is shown within a passage of the book of Joel--as follows:

"Sanctify ye a fast, call a solemn assembly [or Atsereth] " (refer to Joel 1:14 and 2:15). [Note here that for the duration of Atsereth--an all-night vigil would have also been observed--as is shown in the subsequently presented chapter.]

Further examples of the holding of an Asartha (or Atsereth) can be recited from certain chapters of the Bible. In example, a festival that was celebrated in the middle of a lunar month is shown to have required the holding of an Atsereth [= on the 8th day]. This holding of an Atsereth in a lunar month is shown in the following passages: Nehemiah 8:18; Leviticus 23:36; Numbers 29:35; 2nd Chronicles 7:9; John 7:37; and also Deuteronomy 16:8. It is very clear from these passages that the Atsereth was celebrated at the turn of a lunar week [= a lunar quarter].

Thus, the 7 weeks count that is shown by Josephus [= shown to have terminated right at Asartha, on day 50 called Pentecost] was surely predicated upon a count of the lunar week (and not a count of the 7-day week).

CHAPTER 7

ATSARETH ASSEMBLY

The current chapter has a focus upon the routine convening of a sacred assembly among adherents of the Temple system. Of significance here is that each of the Sabbaths that pertained to the 'count-50-cycle' appear to have been understood to stand in the rank of a minor, or a lesser, Sabbath.

The cited tradition of celebrating an Asartha Sabbath can be recited from passages of literature that were circulated in the Temple era--as follows:

"He created the sun and the moon and the stars . . . to rule over the day and the night . . . the sun [was appointed] to be a great sign on the earth for days and for sabbaths and for months . . . the 7th day [was made] holy . . . that day is more holy and blessed than any jubilee day of the jubilees . . ." ('The Book of Jubilees', Chapter 2, translation by R.H. Charles).

It is here significant that an unmistakable reference to the celebration of 'count-50-days' or 'jubilee days' was made by the author. A given conclusion from this historic passage of text is that even though the 7th day was interpreted as "more holy . . . than any jubilee day of the jubilees", some certain significance surrounding the Atsereth appears to have well been understood.

Of related significance here is that a passage from 'The Decalogue' (by Philo Judaeus) pertains to information and knowledge of Sabbath time that was held from prior to the turn of the Common Era. A holy Sabbath; according to the respective Jewish author; appears to have been defined by the lunar week:

"The fourth commandment [= of the Ten Commandments] has reference to the sacred 7th day, that it may be observed in a sacred and holy manner. Now some regions keep a HOLY FESTIVAL once in the month cycle [and then] count from the new Moon each SACRED DAY to God; but the region of Judea keeps every 7th day regularly, after each interval of 6 days . . . " (my paraphrase of Yonge translation).

The record of history thus tends to indicate that some among the primal Hebrews would have interpreted a resting period (or a Sabbath) right in pace with each passing lunar quarter (on the 7th day of every lunar week).

This early-held understanding about the annual harvest being conducted in line with a series of Sabbath rests is also mirrored from writings attributed to a Hebrew philosopher named Aristobulus (3rd century BCE):

". . . the whole world of living creatures, and of all plants that grow, revolves in sevens. And its name 'Sabbath' is interpreted as meaning 'rest'". (Quote borrowed from Gifford's translation of 'Praeparatio Evangelica', Book 13).

Of significance here is the Hebrew record shows the celebration of an all night vigil in association with the 7th lunar Sabbath. During the vigil of this respective Sabbath, certain foods were avoided; and in particular, meat and intoxicating beverages were refrained from.

The celebration of a vigil in association with '50 count' (every 7th Sabbath) can especially be recited from passages of 'de Vita Contemplativa' or 'The Contemplative Life'. (This treatise was written by Philo Judaeus at about the beginning of the Common Era). The respective report has a large focus upon the liturgical practices of a communal group known as the Therapeutae or the Healers. This movement was described to have abandoned commercial enterprise in a fuller pursuit of religious study and prayer--as follows:

" . . . [Therapeutae] may be met with in many places . . . [in] both Greece and the country of the barbarians . . . and there is the greatest number of such men in Egypt.

And in every house there is a sacred shrine which is called the holy place, and the monastery in which they retire by themselves and perform all the mysteries of a holy life, bringing in nothing, neither meat, nor drink, nor anything else which is indispensable towards supplying the necessities of the body, but studying in that place the laws and the sacred oracles of God enunciated by the holy prophets . . .

These men assemble AT THE END of 7 weeks, venerating NOT ONLY the simple week of seven days . . . it is a prelude and a kind of forefeast of the greatest feast, which is assigned to THE NUMBER 50 . . . They come together clothed in white garments . . . they sit down to meat standing in order in a row, and raising their eyes and their hands to heaven . . . they pray to God that the entertainment may be acceptable, and welcome, and pleasing; and after having offered up these prayers the elders sit down to meat, still observing the order in which they were previously arranged . . . And the women also share in this feast . . . And the order in which they sit down to meat is a divided one, the men sitting on the right hand and the women apart from them on the left . . . [They sit on] rugs of the coarsest materials, cheap mats of the most ordinary kind of the papyrus of the land . . .

And in those days wine is not introduced, but only the clearest water; cold water for the generality, and hot water for those old men who are accustomed to a luxurious life.

And the table, too, bears NOTHING WHICH HAS BLOOD, but there is placed upon it bread for food and salt for seasoning, to which also hyssop is sometimes added as an extra sauce for the sake of those who are delicate in their eating . . .

[A sermon is delivered, and when] the president appears to have spoken at sufficient length . . . applause arises from them all as of men rejoicing together at what they have seen and heard; and then some one rising up sings a hymn . . . then they all, both men and women, join in the hymn . . .

Then the young men bring in the table which was mentioned a little while ago, on which was placed that MOST HOLY food, the leavened bread, with a seasoning of salt, with which hyssop is mingled, out of reverence for the sacred table, which lies thus in the holy outer temple; for on this table are placed loaves and salt without seasoning, and the bread is unleavened, and the salt unmixed with anything else, for it was becoming that the simplest and purest things should be allotted to the most excellent portion of the priests, as a reward for their ministrations, and that the others should admire similar things, but should abstain from the loaves, in order that those who are the more excellent person may have the precedence.

And after the feast they celebrate the SACRED FESTIVAL during the whole night; and this NOCTURNAL FESTIVAL is celebrated in the following manner: they all stand up together, and in the middle of the entertainment two choruses are formed at first, the one of men and the other of women, and for each chorus there is a leader and chief selected, who is the most honourable and most excellent of the band. Then they sing hymns which have been composed in honour of God in many metres and tunes, at one time all singing together, and at another moving their hands and dancing in corresponding harmony, and uttering in an inspired manner songs of thanksgiving, and at another time regular odes, and performing all necessary strophes and antistrophes. Then, when each chorus of the men and each chorus of the women has feasted separately by itself, like persons in the bacchanalian revels, drinking the pure wine of the love of God, they join together, and the two become one chorus, an imitation of that one which, in old time, was established by the Red Sea, on account of the wondrous works which were displayed there; for, by the commandment of God, the sea became to one party the cause of safety, and to the other that of utter destruction . . . When the Israelites saw and experienced this great miracle, which was an event beyond all description, beyond all imagination, and beyond all hope, both men and women together, under the influence of divine inspiration, becoming all one chorus, sang hymns of thanksgiving to God the Saviour, Moses the prophet leading the men, and Miriam the prophetess leading the women. Now the chorus of male and female worshippers being formed, as far as possible on this model, makes a most humorous concert, and a truly musical symphony, the shrill voices of the women mingling with the deep-toned voices of the men. The ideas were beautiful, the expressions beautiful, and the chorus-singers were beautiful . . .

[Staying] till morning, when they saw the sun rising they raised their hands to heaven, imploring tranquillity and truth, and acuteness of understanding. And after their prayers they each retired to their own separate abodes . . .

This then is what I have to say of those who are called Therapeutae, who have devoted themselves to the contemplation of nature, and who have lived in it and in the soul alone, being citizens of heaven and of the world, and very acceptable to the Father and Creator of the universe because of their virtue, which has procured them his love as their most appropriate reward, which far surpasses all the gifts of fortune, and conducts them to the very summit and perfection of happiness" (translation borrowed from Yonge).

Of significance about this religious movement is that adherents (who flourished at the turn of the Common Era) are shown to have assembled "in many places". At the 7th week, an all night vigil appears to have routinely been held. The bread and water that was served during the evening banquet was understood to represent "most holy food", and the bread that was eaten is shown to have been mingled with hyssop out of reverence for the sacred table in the vestibule of the Temple.

In reference to the set of religious liturgy subscribed to among the Therapeutae, the holding of a vigil in association with '50 count' can also be recited from the almost contemporary record of Acts:

"And in the day of the Pentecost [50 count] being fulfilled, they were all with one accord at the same place . . . " (Acts, Chapter 2).

The Pentecost event recorded in the book of Acts shows that festival keepers were gathered before "the third hour"--or before 9 o'clock in the morning. The chronology that is given thus implies either a very early morning assembly, or more probably, an evening vigil. In either case, a rather large number of festival keepers are indicated to have been up and about (and they were assembled before 9 o'clock on the Sabbath morning).

Josephus likewise noted that Temple priests who were contemporary with the era of the late 2nd Temple followed a prescribed set of religious liturgy. Of significance here is that the commemoration of the 'number-50 feast' is shown to have required the enactment of predawn ceremony:

" . . . at that feast which we call 'Pentecost' as the priests were going by night into the inner temple as their custom was, to perform their sacred ministrations . . . ". (Quote borrowed from Whiston's translation of Wars, Bk.6:5:3).

The ancient custom of routinely celebrating an all night vigil at the distance of 7 weeks--even in modern times--continues to be celebrated among priests of the Falasha or Ethiopian Jews. For additional information of this priestly vigil, refer to 'The Liturgy of the Seventh Sabbath: a Beta Israel (Falasha) text', by Monica Davis. (Note: The Beta Israel custom is celebrated in association with the traditional 7-day week--not in association with the lunar week).

The indicated assembly for the all night banquet (Asartha) appears to mirror a rather similar all night assembly that is described in the following portion of the New Testament:

"And upon the One-to-the-Sabbaths [or Greek: Mia twn Sabbatwn], when the disciples came together to break bread, Paul preached unto them, IN EXPECTATION (observance) of the coming of morning; and continued his speech until midnight . . . When he . . . had broken bread, and eaten, and talked a long while, even till break of light had come, they brought the young man . . . " (refer to the Greek language version of Acts, Chapter 20: verses 7-12).

Note that because this assembly was held on the One-to-the-Sabbaths then it is somewhat probable that this event was celebrated in association with the renewal of lunar weeks (or the renewal of months). Of related significance is that several instances of this peculiar date 'Mia twn Sabbatwn' [= the One-to-the-Sabbaths] can be recited from New Testament accounts that have detail of the resurrection of Jesus.

This Christian celebration of a feast in line with a lunar schedule (One-to-the-Sabbaths) can additionally be recited from 'The Stromata', by Clement of Alexandria (c. 2nd century CE).

[Peter] inferred thus: "Neither worship as in Judea . . . for in not viewing the Moon, they do not hold the Sabbath, which is called First [= 'One']; nor do they hold the New Moon, nor the Unleavened Bread, nor the Feast, nor the Great Day." (my paraphrase of the fifth chapter).

An early Christian bishop who presided at Jerusalem (Nazianzen) wrote of early Hebrews and Christians tracking and celebrating Sabbath time in the context of a 50 count--as follows:

"The Hebdomads of days give birth to Pentecost, a Day called HOLY . . . and those of years to . . . the Jubilee . . . For seven being multiplied by seven generates fifty all but one day, which we [Christians] borrow from the world to come, at once the Eighth and the First, or rather one and indestructible. For the present sabbatism of our souls can find its cessation there, that a portion [of Sabbath time] may be given to seven and also to eight . . . " ('Oration XLI: On Pentecost', II).

The Christian celebration of an evening rest can, in fact, be recited from Christian literature written as late as the 4th century CE. As an example, Eusebius of Caesarea described how mainstream Christians of his day observed a night vigil in correspondence with a great festival--as follows:

"[Christians observe] a mode of life which has been preserved to the present time by us alone [or by the Christians alone] . . . especially the vigils kept in connection with the Great Festival, and the exercises performed during those vigils . . . [The customs demand] no wine at all, nor any flesh, but water is their only drink, and the relish with their bread is salt and hyssop". ('Church History, Book II').

The peculiar vigil held by Christians at the occasion of a "Great Festival" was also noted by Eusebius to have been a very ancient custom--and THE SAME custom as was adhered to by the Therapeutae.

In the centuries that ensued the destruction of the Temple, the several descriptions of Christians celebrating an EVENING Sabbath (or Asartha) then surely do indicate a continuation of the traditions of former priests.

The cited custom of holding an evening banquet where "most holy food" was served is mirrored from a certain passage of the Colossian's letter--as follows:

"Therefore do not let anyone condemn you in matters of food and drink or of observing festivals, new moons, or sabbaths" (refer to chapter 2:16).

Of significance here is that primal Christians are nowhere shown to have assembled for religious services by any schedule other than was subscribed to by priests who flourished in the era of the Temple. This then means that the cited set of liturgy that pertained to a Sabbath night of rest (and the eating of holy food) would surely have been followed by the earliest of the Christian converts. The ancient tradition of having restricted diet during holy evenings is also rather well mirrored from 2nd-century writings attributed to Justin Martyr. Of significance here is that adherence to a Sabbath ritual with unleavened bread can be deduced from a certain passage of 'Dialogue with Trypho':

"The new law requires you to keep perpetual Sabbath, and you, because you are idle for one day, suppose you are pious, not discerning why this has been commanded you: and if you eat unleavened bread, you say the will of God has been fulfilled."

A commandment to periodically abstain from foods of flesh (meat) is also mirrored from passages of 'The Shepherd of Hermas'. This 1st century publication is unusual in showing the enactment of liturgy in pace with a 'time station':

"[Parable 5:] As I was fasting . . . in the early morning . . . keeping a station . . . [A shepherd told me] "You know not . . . how to fast unto the Lord . . . I will teach you what is a complete fast and acceptable to the Lord . . . If then, while you keep the commandments of God, add these services likewise . . . First of all, keep yourself from every evil word and every evil desire, and purify your heart from all the vanities of this world. If you keep these things, this fast shall be perfect for you. And thus shall you do. HAVING FULFILLED WHAT IS WRITTEN ON THAT DAY ON WHICH YOU FAST YOU SHALT TASTE NOTHING BUT BREAD AND WATER; and from your meats, which you would have eaten, you shalt reckon up the amount of that day's expenditure, which you would have incurred, and shall give it to a widow, or an orphan, or to one in want, and so shall you humble your soul, that he that has received from your humiliation may satisfy his own soul, and may pray for you to the Lord. If then you shall so accomplish this fast, as I have commanded you, your sacrifice shall be acceptable in the sight of God, and this fasting shall be recorded; and the service so performed is beautiful and joyous and acceptable to the Lord. These things you shall so observe, you and your children and your whole household; and, observing them, you shall be blessed; yes, and all those, who shall hear and observe them, shall be blessed, and whatsoever things they shall ask of the Lord, they shall receive."

It here seems pertinent to note that by the time of (or possibly some while after) the 4th century, Christian assemblies began to use the planetary week cycle. Consequently, all of the Christian holy-day festivals were eventually rescheduled to follow a hebdomad itinerary.

The primal Christian adherence to "days of Stations" can further be detected from the contents of a treatise entitled: 'On Prayer'. The authorship of this document is attributed to the 2nd century bishop: Tertullian. Of course, it is somewhat doubtful that the entirety of the text that comprises the current document could have been penned by the original author. The following notation about 'standing' before God's Altar is somewhat unusual in comparison with other Christian literature in that the author of this text explores a possible meaning for the word 'statio' [Latin]:

"Of Stations--Similarly, too, touching the days of Stations, most think that they must not be present at the sacrificial prayers, on the ground that the Station must be dissolved by reception of the Lord's Body. Does, then, the Eucharist cancel a service devoted to God, or bind it more to God? Will not your Station be more solemn if you have withal stood at God's altar? When the Lord's Body has been received and reserved each point is secured, both the participation of the sacrifice and the discharge of duty. If the "Station" has received its name from the example of military life 'for we withal are God's military' of course no gladness or sadness chanting to the camp abolishes the "stations" of the soldiers: for gladness will carry out discipline more willingly, sadness more carefully . . . Prayer is the wall of faith: her arms and missiles against the foe who keeps watch over us on all sides. And, so never walk we unarmed. By day, be we mindful of Station; by night, of vigil. Under the arms of prayer guard we the standard of our General; await we in prayer the angel's trump . . . ".

Writings attributed to the same 2nd century bishop (Tertullian) do furthermore expound upon the Christian tradition of observing stations. The custom among primal Christians of periodically abstaining from certain foods is especially manifested from the contents of a treatise entitled: 'On Fasting--In Opposition to the Psychics':

" . . . [On holy days, Psychics have marital sex, and they hate to fast. However, spiritual discipline requires] reins upon the appetite, through taking, sometimes no meals, or late meals, or dry meals . . . They charge us with keeping fasts of our own . . . Being, therefore, observers of "seasons" for these things, and of "days, and months, and years," we Galaticize. Plainly we do, if we are observers of Jewish ceremonies, of legal solemnities: for those the apostle unteaches, suppressing the continuance of the Old Testament which has been buried in Christ, and establishing that of the New. But if there is a new creation in Christ,' our solemnities too will be bound to be new: else, if the apostle has erased all devotion absolutely "of seasons, and days, and months, and years," why do we celebrate the passover by an annual rotation in the first month? Why in the 50 ensuing days do we spend our time in all exultation? Why do we devote to Stations . . . of the week(s), and to fasts . . . ". (my paraphrase, translation borrowed from S. Thelwall).

Again, there are indications that texts attributed to Tertullian (c. 2nd-century) have been redacted by subsequent scribes. Even so, the cited "devotion to Stations" by the Montanist assemblies seems to have been understood in the context of liturgy subscribed to in an earlier era by the Levitical priesthood.

CHAPTER 8

TRADITION OF A COVENANT

The previous chapter has cited certain historical references in substantiation of an hypothesis that Temple adherents routinely participated in a sacred vigil. The enactment of specific liturgy in pace with a lunar-week schedule raises a number of questions about the origin of the respective custom.

Clearly, the depicted period of an evening vigil was understood to represent time that was holy:

"[Adherents meet together] . . . the young men bring in the table . . . on which was placed that MOST HOLY food, the leavened bread, with a seasoning of salt, with which hyssop is mingled, out of reverence for the sacred table, which lies thus in the holy outer temple . . . And after the feast they celebrate the SACRED FESTIVAL during the whole night . . . " ('The Contemplative Life', Philo Judaeus, translation borrowed from Yonge).

But which one of the laws that are recorded throughout the books of the Bible can even come close to defining an all night gathering? The Sabbath law that is stated to have been penned by God and given to Israel (through Moses) is rather explicit in its definition of a resting day--as follows:

"Six days may work be done; but in the seventh is the sabbath of rest, holy to the LORD . . . the children of Israel shall keep the sabbath, to observe the sabbath throughout their generations, for a perpetual covenant . . . And he gave unto Moses, when he had made an end of communing with him upon mount Sinai, two tables of testimony, tables of stone, written with the finger of God."

Thus, there is no clear evidence that shines from out of the Mosaic law that pertains to the celebration of a Holy Evening. The commandment that is recorded did only stipulate that "in the 7th is the Sabbath".

According to a passage written within 'The Book of Jubilees', the command to work 6 days and then to keep a Sabbath on the 7th day was a tenet known only to the "Angels of the Presence" and also to the "Angels of Sanctification". Furthermore, sanctification was shown to have exclusively been granted to the nation of Israel. In essence, it was understood by the author (or authors) of 'The Book of Jubilees' (c. 150 BCE) that the Heavenly Hosts had sanctified only Israel to celebrate the 7th day:

" . . . He gave us a great sign, the Sabbath day, that we should work six days, but keep Sabbath on the seventh day from all work. And all the Angels-of-the-Presence, and all the Angels-of-Sanctification, these two Great Classes--He hath bidden us to keep the Sabbath with Him in heaven AND ON EARTH. And He said unto us: 'Behold, I will separate unto Myself a people from among all the peoples, and these shall keep the Sabbath day, and I will sanctify them unto Myself as My people. . . And thus He created therein a sign in accordance with which they should keep Sabbath with us on the seventh day, TO eat and to drink, and to bless Him who has created all things as He has blessed and sanctified unto Himself a peculiar people above all peoples, and that they should keep Sabbath together with us . . . Wherefore do thou command the children of Israel to observe this day that they may keep it holy and not do thereon any work, and not to defile it, AS IT IS HOLIER than all other days . . . that day is more holy and blessed than any jubilee day of the jubilees . . . he did not sanctify ALL PEOPLES AND NATIONS to keep Sabbath thereon, but Israel alone: THEM ALONE he permitted to EAT and DRINK and to keep Sabbath thereon on the earth . . . " (Chapter 2, translated by Charles).

Passages from period literature do then stress the significance of keeping the 7th day as a holy Sabbath on the part of Israel. But, why did contemporary adherents of the Temple also interpret the celebration of a minor Sabbath that was "less holy" and "less blessed" than a more major Sabbath.

The most plausible explanation for the holding of a solemn assembly (Atsereth) is probably that this Temple-Era custom was understood to pertain to a covenant that predated the time of Moses. To be more specific, portions of the Genesis record can be recited to substantiate early-held knowledge of an antediluvian covenant--as follows:

"[Chapter 6] . . . [A flood will] destroy all flesh, wherein is the breath of life, from under heaven; and every thing that is in the earth shall die. But with thee will I [= God] establish MY COVENANT; and thou shalt come into the ark, thou, and thy sons, and thy wife, and thy sons' wives with thee. And of every living thing of all flesh . . . shalt thou bring into the ark, to keep them alive . . . ".

This Divine covenant--given to the nations--is listed again in greater detail in the following portion of the 8th chapter:

"Noah builded an altar unto the LORD . . . and offered burnt offerings on the altar. And the LORD smelled a sweet savour . . . and the LORD said while the earth remaineth, seedtime and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease. And God blessed Noah and his sons, and said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth . . . Every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you . . . But flesh with the life thereof, which is the blood thereof, shall ye not eat . . . And God spake unto Noah, and to his sons with him, saying, And I, behold, I establish my covenant with you".

The Genesis account of cataclysm on earth is quite similar to Babylonian records that describe a flood event.

"The Babylonian account of the Deluge in many points closely resembles that of the Bible. Four cuneiform recensions of it have been discovered, of which, however, three are only short fragments. The complete story is found in the Gilgamesh epic (Tablet xi) discovered by G. Smith among the ruins of the library of Assurbanipal in 1872. Another version is given by Berosus. In the Gilgamesh poem the hero of the story is Ut-napishtim (or Sit-napishti, as some read it). surnamed Atra-basis "the very clever"; in two of the fragments he is simply styled Atra-basis, which name is also found in Berosus under the Greek form Xisuthros. The story in brief is as follows: A council of the gods having decreed to destroy men by a flood, the god Ea warns Ut-napishtim, and bids him build a ship in which to save himself and the seed of all kinds of life. Ut-napishtim builds the ship (of which, according to one version, Ea traces the plan on the ground), and places in it his family, his dependents, artisans, and domestic as well as wild animals, after which he shuts the door. The storm lasts six days; on the seventh the flood begins to subside. The ship steered by the helmsman Puzur-Bel lands on Mt. Nisir. After seven days Ut-napishtim sends forth a dove and a swallow, which, finding no resting-place for their feet return to the ark, and then a raven, which feeds on dead bodies and does not return. On leaving the ship, Ut-napistim offers a sacrifice to the gods, who smell the goodly odor and gather like flies over the sacrificer. He and his wife are then admitted among the gods. The story as given by Berosus comes somewhat nearer to the Biblical narrative . . . " ('The Original Catholic Encyclopedia').

In the cited cuneiform record, Ut-napishtim was warned of impending destruction by a god named Ea. (Of interest here is that the Babylonian deity titled as Ea can be recognized to have a name very similar in sound to that of the Biblical God: YHWH). Upon escaping death, Ut-napishtim [= the Chaldean Noah] is shown to have sacrificed to the gods--as follows:

"I sent forth to the four winds,

I poured out a libation

I made an offering on the peak of the mountain:

SEVEN AND SEVEN I set incense-vases there,

Into their depths I poured cane, cedar, scented wood.

The gods smelled a savour,

The gods smelled a sweet savour,

The gods gathered like flies over the sacrificer."

('The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria', Pinches)

Thus, one of the oldest of all religious ceremonies in recorded history is attributed to the Bible patriarch Noah--whose name means rest. In the Babylonian record the sacrificial ceremony was carried out by Ut-napishtim--whose name means life.

Additional perspective concerning God's covenant with Noah can be gained from 'The Book of Jubilees'--the previously cited Jewish document that was in circulation from prior to the Common Era:

"[Chapter 6] And on the new moon of the 3rd month he went forth from the ark, and built an altar on that mountain. And he made atonement for the earth . . . for everything that had been on it had been destroyed, save those that were in the ark with Noah. And he . . . placed a burnt sacrifice on the altar, and poured thereon an offering mingled with oil, and sprinkled wine and strewed frankincense over everything, and caused a goodly savour to arise, acceptable before the Lord. And the Lord smelt the goodly savour, and He made a covenant with him that there should not be any more a flood to destroy the earth; that all the days of the earth seed-time and harvest should never cease; cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night should not change their order, nor cease for ever. 'And you, increase ye and multiply upon the earth, and become many upon it, and be a blessing upon it. The fear of you and the dread of you I will inspire in everything that is on earth and in the sea. And behold I have given unto you all beasts, and all winged things, and everything that moves on the earth, and the fish in the waters, and all things for food; as the green herbs, I have given you all things to eat. But flesh, with the life thereof, with the blood, ye shall not eat; for the life of all flesh is in the blood, lest your blood of your lives be required. At the hand of every man, at the hand of every (beast) will I require the blood of man. Whoso sheddeth man's blood by man shall his blood be shed, for in the image of God made He man. And you, increase ye, and multiply on the earth.' And Noah and his sons swore that they would not eat any blood that was in any flesh, and he made a covenant before the Lord God for ever throughout all the generations of the earth in this month. On this account He spake to thee that thou shouldst make a covenant with the children of Israel in this month upon the mountain with an oath, and that thou shouldst sprinkle blood upon them because of all the words of the covenant, which the Lord made with them for ever. And this testimony is written concerning you that you should observe it continually, so that you should not eat on any day any blood of beasts or birds or cattle during all the days of the earth, and the man who eats the blood of beast or of cattle or of birds during all the days of the earth, he and his seed shall be rooted out of the land. And do thou command the children of Israel to eat no blood, so that their names and their seed may be before the Lord our God continually. And for this law there is no limit of days, for it is for ever. They shall observe it throughout their generations . . . For this reason it is ordained and written on the heavenly tablets, that they should celebrate the feast of weeks . . . to renew the covenant . . . And do thou command the children of Israel to observe this festival in all their generations for a commandment unto them . . . they shall celebrate the festival. FOR IT IS THE FEAST OF WEEKS and the feast of first fruits: this feast is twofold and of a double nature: according to what is written and engraven concerning it, celebrate it. For I have written in the book of the first law, in that which I have written for thee, that thou shouldst celebrate it . . . and I explained to thee its sacrifices that the children of Israel should remember and should celebrate it throughout their generations . . . And all the children of Israel will forget and will not find the path of the years, and will forget the new moons, and seasons, and sabbaths and they will go wrong as to all the order of the years. For I know and from henceforth will I declare it unto thee, and it is not of my own devising; for the book (lies) written before me, and on the heavenly tablets the division of days is ordained, lest they forget the feasts of the covenant . . . they will disturb (the order), and make an abominable (day) the day of testimony, and an unclean day a feast day, and they will confound all the days, the holy with the unclean, and the unclean day with the holy; for they will go wrong as to the months and sabbaths and feasts and jubilees. For this reason I command and testify to thee that thou mayst testify to them; for after thy death thy children will disturb (them) . . . and for this reason they will go wrong as to the new moons and seasons and sabbaths and festivals, and they will eat all kinds of blood with all kinds of flesh." (translation borrowed from Charles, my paraphrase).

The text quoted from 'The Book of Jubilees' has been passed down from a time that reaches far back in recorded history. The topic material covered in this manuscript is significant in that a large focus upon the scheduling of festivals is maintained. It is obvious that the opinion of more than a single author is reflected from the various passages that are disparate. One presented view appears to be upon a calendar of lunar months, another of solar months, and yet another of weeks. Of additional significance about the content of this publication is that the original author of this manuscript was very much concerned that the eternal covenant made with the survivors of the flood (the feast of weeks) would be forgotten in Israel.

This everlasting covenant between God and the nations (or Gentiles) is also mentioned in a prophecy recorded in the book of Isaiah--c. 750 BCE--as follows:

"The earth also is defiled under the inhabitants thereof; because they have transgressed the laws, changed the ordinance, broken the everlasting covenant [Hebrew: olam bereeth]." (AV text of Isaiah 24:5).

More about the significance of this "eternal covenant" with the nations can be understood from passages written in the Talmud. (The Talmud defines modern Judaism, and even though it was written down centuries into the Common Era, the writings are largely based upon what was taught by more primal rabbis).